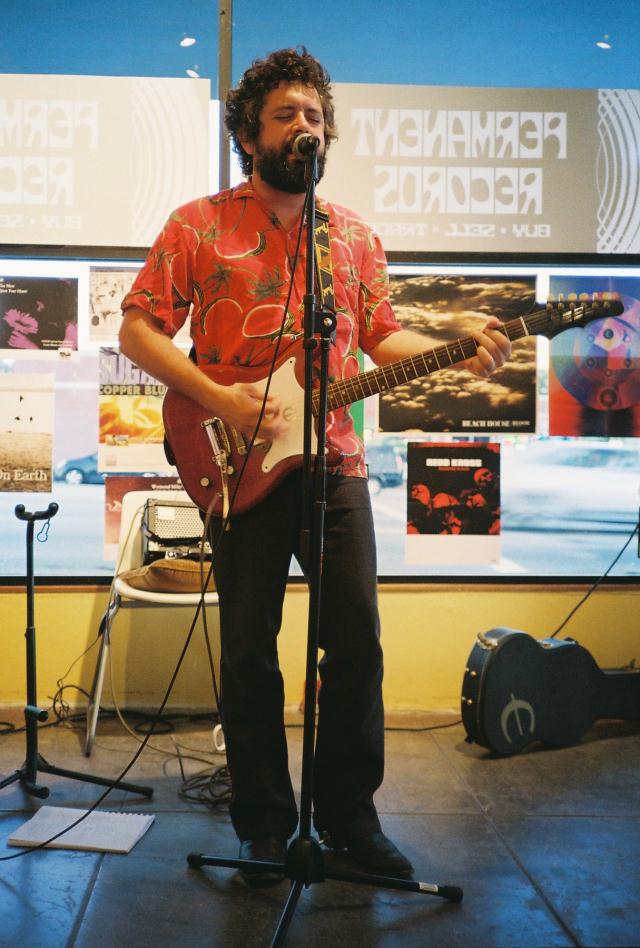

John Wesley Coleman III at Permanent Records

Austin Texas' John Wesley Coleman III plays Razorcake magazine's 69th issue party at Permanent Records in Eagle Rock, California. July 28, 2012.

Photos by Ryan Leach and Mor Fleisher-Leach.

Todd Taylor Interview

Todd Taylor has been writing about DIY culture for more than a decade. After finishing up a master’s degree in literature (in 1996), Taylor started covering music and politics for Los Angeles-based fanzine Flipside. From doing a little bit of everything at the rag—including schlepping issues around L.A. and proofreading interviews—Taylor learned the ins and outs of running a zine—eventually becoming Flipside’s managing editor. After Flipside’s anticlimactic implosion in 2001, Todd started Razorcake fanzine (and Gorsky Press) with friend Sean Carswell. To aid in Razorcake’s efforts to cover esoteric music and polemics, the fanzine received its 501(c)(3) non-profit status in 2005. Razorcake is the first magazine in America dedicated to independent music to bear this distinction.

Razorcake has covered musicians ranging from DIY diehards Dead Moon to Alicja Trout; polemics such as Howard Zinn and Candace Falk (Emma Goldman Project); and punk photographers Dawn Wirth and Ed Colver. Although the magazine covers musicians from all over the world, Razorcake has a strong emphasis on its local East Los Angeles scene; the magazine has run interviews with East L.A.’s Alice Bag and members of bands Los Illegals, the Brat, and Circle One. Razorcake is on the eve of releasing its fiftieth issue.

Interview by Ryan Leach

Leach: Not many people running punk rock fanzines have a master’s degree in English literature. What were you doing in your mid-twenties? What were you envisioning at that age?

Taylor: I got my master’s degree in literature at Northern Arizona University. I then was accepted into the Ph.D. program at the University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesburg. It was a program in literature, but with an emphasis in creative writing—meaning I could still study literature but write a book as my dissertation. So I drove out to Mississippi from Arizona. Unfortunately my personality immediately clashed with the people running the school’s program. It reminded me of some of the problems I had getting my master’s. Shortly after arriving, I called my mom to check up on her. And I found out that my grandmother was really ill. My mother is very deft—she said, “We’re not telling you to do anything, but your grandmother would like it if you stayed with her.” I thought about it for a week and decided I’d rather spend time with someone I really loved than grind it out in a Ph.D. program I didn’t like. My grandmother lived in Camarillo, California—just north of Los Angeles.

After about six months, my grandma got better. I then moved to Los Angeles to get a job. I did odd things…made coffee for a while. I also called up a fanzine I really liked, Flipside. It took them six months to get back to me and their initial questions were: 1.) Do you have a car and a driver’s license?; and 2.) Can you pick up our mail? I told them, “Sure.”

Can you briefly tell me some of Flipside’s history?

One of the amazing things about Flipside was its pedigree. It was started in the summer of 1977 and was continuously publishing until I got there—in 1996. The guy behind the magazine was named Al Flipside. Al was super intelligent. He was one of the zine versions of (venerable KROQ DJ) Rodney Bingenheimer; Al put California punk rock on the map right when it was burgeoning. Since the very beginning—from the legendary Masque shows to what was the present when I arrived.

I started at Flipside at a very low level. But then I moved up. I knew how to proofread. And I started to get very organized. I really learned how to run a fanzine from the inside out. Flipside, for better or worse, had a lot of inertia. So a lot of it worked because the zine had been around for so long, not because it was well run. By the time I arrived, Al was getting burned out. And that’s understandable: he had been at it for a long time. Consequently, he put his energy into other things, like getting a website going when websites were a brand new thing; we were putting out our own films, which was stupidly expensive. Al just liked the process of it.

How long were you at Flipside?

Five years straight.

And then Flipside imploded in 2001.

Yeah. The real brief version—Flipside had its own record label. By pure happenstance Flipside had Beck’s first recorded full length—not the first one out sequentially, but the first he had recorded. Our distributor burned us on the deal—it was selling like hotcakes but he wasn’t paying us. Next thing we know Al’s getting sued by Beck’s lawyers for the money we weren’t receiving from our record distributor. And that was the end of Flipside.

That must have hit you hard. You had worked indefatigably for Flipside.

I was traumatized, walking around in a stupor for about a month. I was physically conditioned to getting up in the morning and working on the magazine. Literally everything that I had been working up towards was gone. I played around with the idea of starting a website after Flipside ended. By that time it was pretty cost effective. And I wanted to get something up. Although I wanted to do something completely different from Flipside, I still wanted to contribute something to the legacy of Flipside. My friend Skinny Dan and his wife put together the first round of Razorcake’s website. I was also able to get some of the people at Flipside (Liz O., Kat Jetson, Jimmy Alvarado, etc.) to come over with me. I was really the contact point for a lot of Flipside’s writers toward the end, so it wasn’t that hard to get them together.

How long did Razorcake the website exist before Razorcake the fanzine came into existence?

For only about three months. Although I think the internet is a great tool, my heart wasn’t really into a website. I wanted to do a print magazine again. I got in contact with my friend Sean Carswell, who I had gone to college with in Arizona, and told him my ideas. He agreed to move out to California to help me with Razorcake—but only if we’d get the magazine version going. It was a big commitment for him because he was just about to get married; he had a lot going on in his life.

How did you create a print magazine that was self-sustaining and published regularly from the get-go? I know you had very little funding.

It all had to do with my work at Flipside. I knew the printer, the subscribers, the writers, and the advertisers. And because I knew the problems at Flipside, I could kind of work them out as Razorcake in its magazine form started going. Of course a lot of these problems were very painful. Creating a database is very boring, but it makes sure you’re on top of things.

One of my favorite early interviews in Razorcake had little to do with music at all: your (and Sean’s) interview with Howard Zinn.

Looking back—some stuff is amazingly simple. Sean and I were putting out a book (through their small publishing company, Gorsky Press) by an author in Boston. And we made a list of points of interest in Boston. On the top of that list was “the place where Howard Zinn teaches!” I think we just emailed him. That was it. And he was very gracious.

Prior to going to Boston, Sean Carswell had just written a book. Sean had sent it to Howard before we went. As we were leaving the interview with Howard, Sean very sheepishly asked, “Hey, Mr. Zinn, do you get a chance to look at my book?” Howard opens up his briefcase and takes the book out. And it’s marked with some sort of notation—post-it notes kind of thing. He told Sean, “You know, I really enjoyed it.” Sean was just floored.

I’m hard pressed to find a higher accolade!

Howard was great. Here’s a guy who is in his late 70s or early 80s. And he is just so spry. He still takes the stairs. Howard is incredibly quick and very funny. He just took an hour and a half out of his day to talk to two schlubs.

Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St. Clair put out an amazing collection of essays called End Times: The Death of the Fourth Estate. As the title suggests, the essays in the book revolve around corporate media’s failure to provide reliable information to the public. While this knowledge is nothing new, Cockburn and St. Clair’s writings are enlightening in their detail of just how uncertain these corporate elites are about their own future. I’ve always felt magazines have more stability—and could better encourage long-term critical writing—with a non-profit status. And you can see that in publishing houses like AK Press and South End Press; and magazines like Monthly Review and Z. Can you tell me about your decision to go non-profit?

Yeah. Since day one with Razorcake we’ve really paid attention to our finances. It’s out of necessity. No one has a pot of money we can dip into. And none of us have any sort of courage with credit cards. I don’t think, “Hey, if I do this one thing, in two months I can make all this money.” I just don’t have that sort of mentality. So we just kept looking and looking at things that were going well and things that were dying. And a thing that was dying was traditional magazine distribution. We also didn’t want to raise our ad rates. Because then we would have to change our focus. So for instance we would then have to allow bands that are corporately funded into our magazine due to increased rates. Or maybe we’d have to incorporate this loosely lifestyle stuff. Like beer ads. And that would be our death sentence. So we had to figure out how to keep costs down or how to better maximize what we had. We were like squirrels trying to crack open this nut. We kept thinking and thinking. I honestly can’t tell you the exact moment where we seriously thought about becoming a non-profit. But it was one of those things where—just because it hadn’t happened to someone in our position before—we didn’t think that it was impossible. Meagan Pants (a regular contributor to Razorcake) was really instrumental in the process. So we just looked at our situation and the situation of print media over and over again. We just thought, “Hey, we can do this. And it’s totally justifiable. We’re not lying to anyone.” But the things that we do naturally on a day-to-day basis fit a non-profit model. They just haven’t been put together before. For instance we have bands stay at our house. We throw shows. It’s a really viable subculture that’s incredibly overlooked. The bands making this music—they’re living poor. You have enough money to go on tour. But then you realize all the money made went into funding the tour.

And you have to take into consideration the fact that these musicians are not receiving any kind of governmental subsidy. It’s not like Scandinavia—where bands have received economic support from their respective governments.

There is no funding for musicians in the States. To be an independent artist—people here look at that like, “Oh, you’re not successful enough to be a corporate-backed artist.” It’s like a Social Darwinism. These artists have made conscientious choices not to act a certain way. And instead of being lauded for it, they’re further punished. Nothing against manual labor—I totally see the nobility in it—but people who make music, who write about music, we’re looked at as scoundrels. We’re “trying to avoid hard work.” And that’s simply not the case. A large component of American life is eroding. We’re at a point now where the mindset is, “Oh, you’re not smart enough to get sponsorship by an energy drink. That’s your fault.”

You can see that in education too. The way educators are paid and how poorly public schools are funded. Schools are now encouraged to get the soft drink endorsements…to put in the vending machines.

Exactly. Libraries are another example. Most of the institutions in the public sector you cannot base on a financial system. These are twenty year returns that will yield incredible benefits down the road. But there’s no patience for that anymore. On that note, we at Razorcake don’t care who is on the cover of our zine. It’s not like a certain artist on the cover is going to sell us two to three times more issues. That became clear to me when we put a band called Against Me! on the cover one issue. They were starting to become very popular at around the time the issue came out. On the next issue we put Alicja Trout on the cover. Not as many people know about Alicja—an awesome lady from Memphis who has been in a ton of bands and runs her own distribution label. Nevertheless the two issues sold almost identically. It takes a long time to have a relationship of trust with readers. I would rather have that trust than to try and cash in on putting some Warped Tour band on the cover of Razorcake. That’s hard for people to understand.

You’ve done interviews with bands that don’t even have a record out. So much of our culture is commodity driven. That’s really incredible. I can’t think of too many other music magazines that would do something like that.

I still have this romantic notion that music has the ability to soothe; and that it’s a good force in and of itself. Even if it expresses agony. Music has a soul to it. And it doesn’t have to do with physical appearances or superficialities. We deal with stuff that has been castoff. The music we cover is ethnically and geographically diverse.

One thing that I think works in Razorcake’s favor is the variety of musicians covered. Although the magazine kind of falls under a punk rock umbrella, Razorcake has covered musicians like rockabilly eccentric Hazel Adkins. There doesn’t always seem to be a stylistic nexus between some of the interviews in the magazine, yet it all works.

I just trust our writers. I’ve been dealing with some of the same writers in a creative way for more than a decade. I know them and they know me. And if something is of interest to them—enough for them to dedicate a lot of time to it—then I’m interested in what they’re going to say. It keeps things interesting. Even if I disagree with them.

Getting back to your non-profit status, can you briefly tell me about the process of receiving that distinction?

I’m interested because as you were saying earlier, Razorcake doesn’t fit the traditional paradigm of a non-profit.

The process was grueling. Again, we were trying to do something that hadn’t been done before. Literally, if we said that we were going to have a non-profit theatre in our community—and had shown them the need for it—they would’ve known how to respond to that. It ended up taking two years and we had literally four inches of paperwork. We went through three rounds. The first round—twenty questions. The second—ten. The third—four. And I have a degree in literature, I knew what the words were in the questions they were asking us, but I had no idea what they were asking. No clear understanding of the legal jargon. So we went to a non-profit entertainment lawyer and he decoded the paperwork for us. They were concerned: “Why don’t you want to make money? Music magazines are on a business model for making money.” And we had to explain it to them very explicitly that we were not interested in making money. That we were interested in promoting artists who we felt were great, but weren’t economically very alluring to other music magazines. It was very weird. It was like self-examining your own life. And explaining these things to beaurocrat in Middle America—who has no idea about what punk rock is about—was very surreal.

In the last two years I’ve noticed that you’ve really branched out. I know you’re currently trying to get an all-ages venue going in East Los Angeles. You’ve also just gotten some podcasts underway and recently put out a few 7”s. Your non-profit status seems to have really galvanized you into trying to do more…

Very much. My favorite things in the world are listening to music and writing. The magazine is the perfect synthesis of those two things. But I’ve learned that maybe we can share this stuff with other people—that’s where the podcasts come in. And we’re not an ideology, we’re not dogmatic—so here’s a bunch of things our writers like that you might like too. There’s this misunderstanding that the internet can meet all your needs. Nothing could be further from the truth. And we started doing records under the auspices of the non-profit. It’s just accounting. The band gets a certain amount of money. We sell the record for a certain amount. Razorcake recoups its loses. And we’re done. Again, we’re just trying out new things to promote music from people who are off the radar. It’s a lot of work—we’re doing things that haven’t been done before—but it’s certainly worth it.

For more information, check out: www.razorcake.org

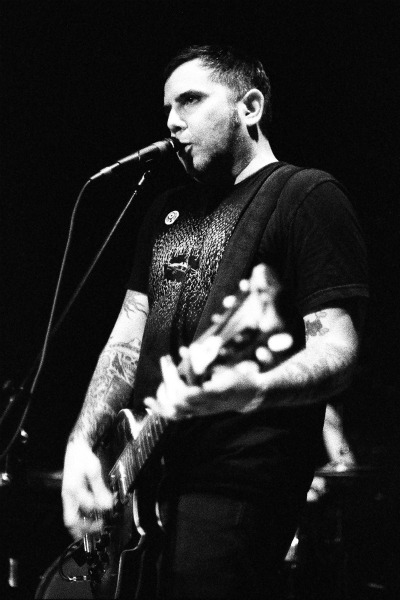

Hex Dispensers Photos

Austin Texas' Hex Dispensers play Razorcake magazine's 10th anniversary benefit show at American Legion Hall in Highland Park, California. August 12, 2011.

Black and white photos shot with Ilford 3200 film. 800 ISO film for the color shots.

Photos by Ryan Leach and Mor Fleisher-Leach.